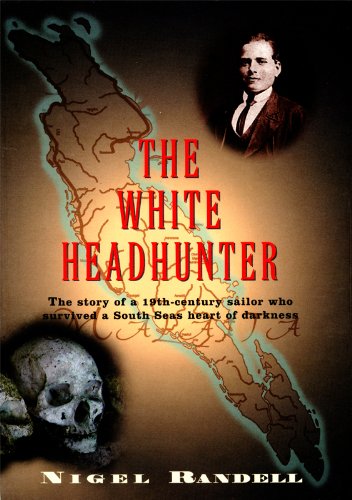

I'd highly recommend Nigel Randell's book The White Headhunter: The story of a 19th century sailor who survived a South Seas' heart of darkness (2003). It's incredibly well-researched, informative and I found it very easy to read.

The sailor in question was Jack Renton, a young man from the Orkney Islands who was press-ganged into working on a ship bound for the Pacific Ocean. Finding himself in hellish conditions extracting guano on a remote island in (what is now) Kiribati, he and several other men escaped and spent weeks drifting across the Pacific until they finally made landfall in Malaita, in the Solomon Islands.

|

| Randell's The White Headhunter (2003) |

Perhaps the most sensational parts of Renton's story (his involvement in war parties, headhunting and his marriage to a local Malaitan woman) were glossed over, being considered subjects that were too sensitive for his 19th century audience.

People were much more interested in hearing about how savage the tribes were in Malaita, which already had a reputation for being one of the most dangerous places in the world.

Randell's theory is that it wasn't a black and white case of 'civilised white man forced to live with savages' but, rather, that Renton experienced a lot of kindness from the native people of Sulufou; he learnt their language and came to understand a culture steeped in centuries of tradition.

In fact, after a visit home to his native Orkney Islands, Renton missed the Pacific so much that he returned to Australia to take up a post inspecting ships that were sourcing Pacific labourers for work in Queensland's sugar cane plantations.

In fact, after a visit home to his native Orkney Islands, Renton missed the Pacific so much that he returned to Australia to take up a post inspecting ships that were sourcing Pacific labourers for work in Queensland's sugar cane plantations.

The press-ganging of native Pacific Islanders to work in Queensland, known as blackbirding, was quite common in the mid-19th century. Ruthless blackbirders took advantage of the Pacific Islanders' desire to trade and they tricked men and women to come on-board their ships, so they could remove them from their native islands and transport them to a life of hard labour in Queensland.

|

| Pacific Islanders being freed from a blackbirding ship State Library of Victoria, file on Wikipedia |

Some blackbirders even masqueraded as Missionaries, because they knew that Missionaries had a relatively good reputation in places like the New Hebrides (modern-day Vanuatu), until it got to the point that the Pacific Islanders felt they could trust no-one and there were several cases where bona fide Missionaries were murdered, because the Islanders thought they were blackbirders.

By the time Renton was rescued from Malaita, the recruitment of labour from the Pacific Islands had settled down somewhat into, more-or-less, acceptable three-year contracts. Once the Islanders understood that they would be able to earn some money and return home after their contracts expired, there was a lot more interest in travelling to Queensland for work.

What I loved about the way Randell did his research was that he used parallel narratives, i.e. both European sources, such as the many 19th century Beachcomber memoirs and the oral traditions of the Islanders themselves. It's interesting to note how the Islanders' oral accounts of Renton's time on Malaita, differ somewhat from the more official European version of his time on that island.

|

| Footprint in the sand, from my own photos |

Some of them ended up in the Pacific as a result of shipwreck, others chose to live on Pacific Islands, in order to escape enforced labour or imprisonment in the new British penal colony of New South Wales. They played an interesting inter-cultural role, as contact between Europeans and the Pacific Islanders developed and I couldn't help but think again of the flip side of Solomon, i.e. the Queen of Sheba and the birth of international diplomacy.

Randell also writes a lot about the establishment of Missionary stations in the Pacific and the power and influence that Missionaries eventually gained. Renton's friend, Kwaisulia, who eventually became the 'big man' in Sulufou, was dismissive of Christianity, but there was something inevitable about the advent of European traditions in the Pacific.

Nowadays 92% of people in the Solomon Islands profess Christianity as their religion, with only 5% of people following traditional animist beliefs (funnily enough, most of these are on Malaita!)

Nowadays 92% of people in the Solomon Islands profess Christianity as their religion, with only 5% of people following traditional animist beliefs (funnily enough, most of these are on Malaita!)